Midrashim for Yamim Noraim

Prof. Ruchama Weiss following the Sages of the Talmud

Ruchama Weiss is a Professor of Babylonian Talmud, a poet, and a publicist. She publishes a weekly column in the press on the weekly Torah portion and current affairs in the Ynet-Judaism section.

The Institute for Jewish Studies Barcelona (EJB) presents selected translations of these columns courtesy of Prof. Ruchama Weiss and Ynet.

Demolition in the Al-Tuffah neighborhood in Gaza City. (Photo: Omar Al-Qattaa / AFP) Ynet

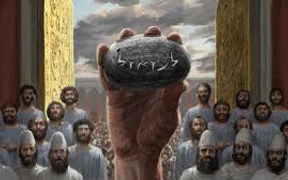

05.09.25 To Erase the Memory of Amalek: How do you say “genocide” in Jewish terms? In the past two years we have been poisoned by calls likening Gaza to Amalek. Jewish sources teach that this is not only horrifying, but also that it does not work: genocide is fantasy, not reality. This understanding emerges both from the biblical story and from a marvelous aggadic tale in the Talmud about descendants of Haman who ended up in Bnei Brak. Let us speak about Gaza I postpone this subject week after week; it is too painful for me, but we cannot avoid addressing voices calling to ignore the suffering in Gaza and even to annihilate it utterly. It is not possible to claim these are merely cries against “weeds,” because such calls come from some of Israel’s most senior figures. How do you say “genocide” in Jewish terms? In the past two years our Jewish psyche has been poisoned by calls for the destruction of an entire population: “to cleanse Gaza,” “to destroy Gaza,” “to flatten Gaza,” “there are no innocents in Gaza,” and so on. True to the issues I deal with, I will focus on one horror among many — the argument constructed on Jewish sources: equating “Gaza” with “Amalek. The Israeli leadership elite uses the name “Amalek” as if it were an internal code and assumes the Christian world, whose support Israel desires, will not understand the meaning. At the start of the war the prime minister said: "זכור את אשר עשה לך עמלק" — “Remember what Amalek did to you,” "נצטווינו. אנו זוכרים, ואנו נלחמים". — “we were commanded. We remember, and we fight.” Later, when the comparison to Amalek was raised before the court in The Hague, Netanyahu’s office tried to clarify that “there was no intention to incite genocide of the Palestinians, but rather to describe the horrific massacre carried out by Hamas terrorists on October 7 and the need to fight them.” Knesset member Boaz Bismuth abandoned coded language and precisely described the commandment he believes should be carried out in Gaza: “We must not forget that even the ‘innocent civilians’ — the cruel and monstrous people from Gaza — took an active part in the pogrom inside Israeli settlements, in the systematic murder of Jews... We must not pity the cruel; there is no place for any humanitarian gesture — we must wipe out the memory of Amalek.” Rabbi Shmuel Eliyahu, chief rabbi of Safed, declared: “The law regarding the Arabs in Gaza is as the law regarding Amalek and one must carry out upon them the commandments of obliterating the memory of Amalek.” Many others, prominent and numerous, echoed the biblical command to annihilate a people, and I will close this partial list of quotations with the shameful slogan shared by Yinnon Magal: “And in one command we are bound: to wipe out the seed of Amalek... everyone knows our slogan: there are no innocents.” Let there be no misunderstanding Genocide is a cross-cultural fantasy, and it also appears in our Book of Books. The Torah contains an explicit command to utterly annihilate a people: men, women, girls and boys, the old and the young, and even animals. If that were not enough, the command is mentioned twice: "וַיֹּאמֶר ה' אֶל מֹשֶׁה כְּתֹב זֹאת זִכָּרוֹן בַּסֵּפֶר וְשִׂם בְּאָזְנֵי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ כִּי מָחֹה אֶמְחֶה אֶת זֵכֶר עֲמָלֵק מִתַּחַת הַשָּׁמָיִם... וַיֹּאמֶר כִּי יָד עַל כֵּס יָהּ מִלְחָמָה לַה' בַּעֲמָלֵק מִדֹּר דֹּר". (שמות י"ז, י"ד–ט"ז) “And the Lord said unto Moses, ‘Write this for a memorial in the book, and rehearse it in the hearing of Joshua: that I will utterly blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven…’ … ‘For the hand is upon the throne of the Lord; the Lord will have war with Amalek from generation to generation.’” And again: "זָכוֹר אֵת אֲשֶׁר עָשָׂה לְךָ עֲמָלֵק בַּדֶּרֶךְ בְּצֵאתְכֶם מִמִּצְרָיִם, ... תִּמְחֶה אֶת זֵכֶר עֲמָלֵק מִתַּחַת הַשָּׁמָיִם, לֹא תִּשְׁכָּח". (דברים כ"ה, י"ז–י"ט) “Remember what Amalek did unto thee by the way, when ye were come forth out of Egypt… Thou shalt blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven; thou shalt not forget.” The command is written in words that leave no room for doubt: to blot out “the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven,” “war to the Lord with Amalek from generation to generation.” This is not a defensive war, nor a war of conquest, nor even a revenge war intended to terrify — it is complete annihilation, multi-generational, of Amalek and all that recalls him. It does not work Genocide is a childish fantasy (even when endorsed by adults) that divides the world into “children of light” and “children of darkness,” with “us” always in the light and “the other” in darkness. This is not only shocking, it also does not work — and we, the Jewish people, are the example. Many tried to annihilate us and never succeeded. I am ashamed to write, because I know that by writing arguments against genocide I may inadvertently become part of a legitimization process. But I feel obliged to address the sources that are, alarmingly, gaining popularity today. It is important to clarify that the Jewish sources that commanded the extermination of Amalek undercut themselves, and they teach that genocide is fantasy, not reality. Samuel the prophet sends the first Israelite king, Saul, on his important mission (I Samuel 15:3): "עַתָּה לֵךְ וְהִכִּיתָה אֶת עֲמָלֵק וְהַחֲרַמְתֶּם אֶת כָּל אֲשֶׁר לוֹ וְלֹא תַחְמֹל עָלָיו, וְהֵמַתָּה מֵאִישׁ עַד אִשָּׁה מֵעֹלֵל וְעַד יוֹנֵק מִשּׁוֹר וְעַד שֶׂה מִגָּמָל וְעַד חֲמוֹר". — “Now go and smite Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have, and spare them not; but slay both man and woman, infant and suckling, ox and sheep, camel and ass.” A clear and cruel command: annihilate every infant and even the animals, so that no remnant of Amalek remains. The cynicism of mercy The Bible describes the results with sharpened cynicism (ibid., v.9): "וַיַּחְמֹל שָׁאוּל וְהָעָם עַל אֲגָג וְעַל מֵיטַב הַצֹּאן וְהַבָּקָר". — “But Saul and the people spared Agag, and the best of the sheep and of the oxen, and the fatlings, and the lambs, and all that was good...” They did not show mercy; they coveted the best livestock and preferred booty to destruction. And the king? Commentators debate why Saul did not kill Agag. Self-interest seems a more convincing motive than “mercy” that flows amid rivers of blood for Amalek’s infants. The ending is known: Samuel is angry in God’s name, Saul begins to lose the throne, and what of King Agag? In the story’s close he is executed by Samuel. Seemingly, after Agag’s slaughter all Amalek has been wiped out and there is no longer a need to blot out Amalek — yet a few chapters later, after a decisive victory and “complete annihilation,” King David wages war against Amalek (I Samuel 27:8): "וַיַּעַל דָּוִד וַאֲנָשָׁיו וַיִּפְשְׁטוּ אֶל הַגְּשׁוּרִי וְהַגִּזְרִי וְהָעֲמָלֵקִי". — “David and his men went and smote the Geshurites, the Girzites, and the Amalekites.” The devil of history smiles: this was not a divine command that can be enacted as stated; it is a moral test, and we failed in both directions: we committed a crime, and we failed to complete it. And if we hang Haman and his sons? Generations passed, the Temple was destroyed, and we became a people “scattered and dispersed among the nations,” yet we did not give up the fantasy of wiping out Amalek. The Book of Esther tells of a meeting between a descendant of King Saul, "מָרְדֳּכַי בֶּן יָאִיר בֶּן שִׁמְעִי בֶּן קִישׁ אִישׁ יְמִינִי" — “Mordecai son of Jair son of Shimei son of Kish, of the tribe of Benjamin” — and a descendant of Agag the Amalekite, "הָמָן בֶּן הַמְּדָתָא הָאֲגָגִי" — “Haman son of Hammedatha the Agagite.” Mordecai tries to show strength against the descendant of the king whom Saul did not destroy. But Mordecai lacks political power (as yet) and has no weapon (yet), and he takes a proud and dangerous step that causes the sword of annihilation to turn its direction and suddenly the Jewish people face existential danger. Esther risks her life and saves the Jewish people, but much damage has already been done and the streets run with blood. And yet still the Amalekites are not annihilated. Because there is no such thing as genocide. There are demonic and childish attempts to exterminate peoples, and we must put an end to them. Eight words worth gold Oh, how wise the Sages were. The Mishnah and Talmud were formed at a time when we were not sovereign, and many thought it undesirable to return to that status, for we had learned the price of blood that sovereignty exacts. In the heart of the series “Legends of the Destruction,” and with humor born of deep worldly wisdom, the Sages wove in this information (Babylonian Talmud, Gittin 57b): "מבני בניו של המן למדו תורה בבני ברק". — “From the sons of the sons of Haman they learned Torah in Bnei Brak.” This short quasi-historical legend is worth its weight in gold. It undermines the biblical command and adds a moral practical layer: there are no fundamentally evil people, and there is no fundamental difference between us and Amalek. If an Amalekite can be a learned scholar, then a learned scholar can become an Amalekite. Nothing is more broken than a whole heart We were all created with exactly the same measure of the divine image, and therefore Agag’s childhood deserves life just like our childhoods do; they can even study at the same university (this, the Sages said). Whoever is not even a little terrified by the hunger and death in Gaza should go to a cardiologist. Whoever sends soldiers to kill and to die, abandons hostages and “sleeps with a clean conscience,” needs a heart transplant. Our conscience should not be clean; it should work with materials that are not sterile. We have no reason to sleep quietly, for we must bring back the hostages and end the war. This is upon our conscience, and we have the capacity to do it.

From the film “Legend of Destruction”

(Illustration: David Polonsky and Michael Faust)

01.08.25 Betting Everything: The Messianism that Endangers Us, from Destruction Until Today Not all messianism is dangerous, but when a messianic fantasy fuses with weapons and charisma, a bloodbath will follow. Among the sages of the Talmud were zealots such as Rabbi Akiva, who believed in an “all or nothing” approach in the struggle against the Romans. In retrospect, zealotry brought disaster, while the conciliatory approach saved Jewish culture. What can we learn from this for the present war? From the film “Legend of Destruction” (Illustration: David Polonsky and Michael Faust) The term “messianism” is a central player in any attempt to explain the State of Israel during the War of Iron Swords. On the eve of Tisha B’Av—the day of mourning for the many destructions intertwined with messianism—it is fitting to reflect on the history of Jewish messianism. The biblical messiah is straightforward to understand and digest. A messiah is one who has been anointed with the sacred oil. At the outset, anointing was a way to testify to a divine choice for service in the holy. The first to be anointed were Aaron and his sons (Exodus 28): "וְלִבְנֵי אַהֲרֹן תַּעֲשֶׂה כֻתֳּנֹת... וְהִלְבַּשְׁתָּ אֹתָם אֶת אַהֲרֹן אָחִיךָ וְאֶת בָּנָיו אִתּוֹ וּמָשַׁחְתָּ אֹתָם... וְקִדַּשְׁתָּ אֹתָם וְכִהֲנוּ לִי". “And for Aaron’s sons you shall make tunics… And you shall clothe them—Aaron your brother and his sons with him—and you shall anoint them… and you shall consecrate them, that they may minister to Me as priests.” Later, we find the prophets anointing kings. Thus it was done with Saul (I Samuel 10:1): "וַיִּקַּח שְׁמוּאֵל אֶת פַּךְ הַשֶּׁמֶן וַיִּצֹק עַל רֹאשׁוֹ וַיִּשָּׁקֵהוּ וַיֹּאמֶר הֲלוֹא כִּי מְשָׁחֲךָ ה' עַל נַחֲלָתוֹ לְנָגִיד". “Then Samuel took the vial of oil and poured it upon his head, and kissed him, and said: Has not the Lord anointed you to be prince over His inheritance?” After him, and in his place, David was anointed. Later still, the concept weakened, and when God “dismisses” the prophet Elijah, He instructs him (I Kings 19:15): "וּבָאתָ וּמָשַׁחְתָּ אֶת חֲזָאֵל לְמֶלֶךְ עַל אֲרָם". “Go, and anoint Hazael to be king over Aram.” It is unclear how a prophet is to anoint a foreign king, and certainly this is not a “messianic” event. As the 15th-century commentator Don Isaac Abarbanel explains: "לא היה חזאל ולא שאר מלכי אומות העולם נמשחים... אבל מאשר היה מינוי המלוכה על ידי משיחה, הושאלה לשון המשיחה לכל מינוי וגדולה". “Neither Hazael nor the other kings of the nations were anointed… but since the appointment of kingship was done through anointing, the term ‘anointing’ was borrowed for every appointment and elevation.” Once exile came and the days of anointing priests and kings ended, anointing shifted from a letter of appointment to a dream, and from a dream to an ideology. Messianism became a striving—perhaps at any cost—for the day when we might once again anoint a king over us. The Psychological Explanation The religious-national dream is one side of the explanation. The other lies in the psychology of the individual. Years ago, I spoke with child psychologist Rami Bar-Giora, who offered a simple explanation for belief in redemption: when a newborn feels hunger, the sensation of danger and death floods her entire being. If all goes well, a few minutes after she begins to cry she feels warm, sweet liquid that brings complete calm. In an instant, her life moves from disaster to redemption. Thus, explained Rami, the dream of redemption was embedded in us. This experience of an instant shift—from disaster to redemption, and from redemption back to disaster—also characterizes our foundational cultural story: we were in “Paradise,” we were cast out in a moment, and our dream is to return. Why Messianism is Dangerous As long as a fantasy of redemption leads me only to take out a big loan at the bank, or to sign up for a diet, fitness, coaching, or fortune-telling program that promises to change my life beyond recognition, I am dealing with messianic thinking in my private world and endangering almost only myself. Beyond that, the danger is usually not severe. Even at the national level, not all messianism is dangerous. As long as we dream: "הָשִׁיבָה שׁופְטֵינוּ כְּבָרִאשׁונָה וְיועֲצֵינוּ כְּבַתְּחִלָּה... וּמְלוךְ עָלֵינוּ מְהֵרָה... בְּצֶדֶק וּבְמִשְׁפָּט... וְכָל הַזֵּדִים כְּרֶגַע יאבֵדוּ, וְכָל אויְבֶךָ וְכָל שׂונְאֶיךָ מְהֵרָה יִכָּרֵתוּ". “Restore our judges as at first, and our counselors as in the beginning… reign over us soon… in justice and in righteousness… and may all the wicked be destroyed in a moment, and may all Your enemies and all who hate You quickly be cut off.” —we remain in the realm of fantasy, which may be unhealthy at times but need not be dangerous. But when messianic fantasy fuses with weapons and charisma, a bloodbath ensues. Messianism scorns reality and seeks to replace it with “the days of the messiah,” and thus money, health, and even life itself become irrelevant—or worse: taking them into account only deepens the sinking into the present and delays redemption. In contrast to messianism stands the demand to accept reality as it is. This need not be a depressive stance (though that deserves a separate discussion). One raised in messianic thought will need great spiritual work to replace it with acceptance of reality. Disputes Written in Blood In the first and second centuries CE, the Land of Israel and the Jewish communities were flooded with messianic ideas. Christianity emerged, apocalyptic literature was written, and the Romans offered no “secular” cure. At least three times we preferred messianism to reality—the Great Revolt, the Diaspora Revolt, and the Bar Kokhba Revolt—and in all three we paid with rivers of blood. The disputes written in blood nearly two thousand years ago resemble today’s debates between messianism and realism (Babylonian Talmud, Avodah Zarah 18a): כשחלה רבי יוסי בן קיסמא, הלך רבי חנינא בן תרדיון לבקרו. אמר לו: חנינא אחי, אין אתה יודע שאומה זו (רומא) מן השמיים המליכוה? שהחריבה את ביתו ושרפה את היכלו, והרגה את חסידיו ואבדה את טוביו, ועדיין היא קיימת, ואני שמעתי עליך שאתה יושב ועוסק בתורה ומקהיל קהילות ברבים וספר מונח לך בחיקך. אמר לו: מן השמיים ירחמו. אמר לו: אני אומר לך דברים של טעם, ואתה אומר לי מן השמיים ירחמו, תמה אני אם לא ישרפו אותך ואת ספר תורה באש. When Rabbi Yose ben Kisma fell ill, Rabbi Hanina ben Teradyon went to visit him. He said to him: “Hanina my brother, do you not know that this nation (Rome) was given kingship from Heaven? It destroyed His house, burned His sanctuary, killed His pious ones and destroyed His good ones, and yet it still endures. And I have heard of you that you sit and occupy yourself with Torah, gathering assemblies publicly, and a scroll of the Torah rests in your lap.” He replied: “Heaven will have mercy.” He said to him: “I speak to you words of reason, and you say ‘Heaven will have mercy’? I wonder if they will not burn you and the Torah scroll in fire.” In the role of the messianic leader: Rabbi Hanina ben Teradyon. In the role of the realist leader: Rabbi Yose ben Kisma. Both were sages and believers, teaching us that the debate over messianism takes place within the religious world itself (and still today within religious Zionism, while Haredim are usually not practically messianic). Rabbi Yose ben Kisma accepts reality even when it harms him. In his view, reality expresses the will of God: "אומה זו מהשמיים המליכוה". “This nation was given kingship from Heaven.” Therefore, one must not strive for an alternative reality. Rabbi Hanina ben Teradyon, by contrast, sees reality as a challenge that must be overcome at any cost. Ben Kisma believes one should bow the head and wait for the storm to pass, while ben Teradyon rides the storm toward redemption. Ben Kisma worries about the loss of life; ben Teradyon scorns such concern. The editor of the Talmud sides with Ben Kisma’s moderate stance, since when Ben Teradyon was executed the Torah was burned with him. We thus learn: one who scorns life also scorns Torah. How Do We Define Foolishness? A similar debate appears in the famous tradition about the departure of Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai from Jerusalem to Yavne. According to the legend, when the Romans besieged Jerusalem and hope was lost, Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai left the city, met the general Vespasian, and told him he was destined to become Caesar. When the prophecy was fulfilled, Vespasian offered him a request. Ben Zakkai asked (Babylonian Talmud, Gittin 56b): "תן לי יבנה וחכמיה". “Give me Yavne and her sages.” To this Rabbi Akiva (and some say Rav Yosef) responded with the verse (Isaiah 44:25): "'משיב חכמים אחור ודעתם יסכל'". “He turns wise men backward and makes their knowledge foolish.” In other words, he should have asked him to lift the siege from Jerusalem. But Rabban Yohanan thought: perhaps he will not even grant this smaller request, and then there will be no salvation at all. Rabbi Akiva—who is said to have seen Bar Kokhba as the messiah—called the conciliatory ben Zakkai a "סכל" (“a fool”). He thought ben Zakkai should have asked to remove the siege from Jerusalem. The narrator explains that ben Zakkai thought Vespasian would not agree to such a great request, and therefore he settled for Yavne. Was Rabbi Akiva naïve, believing that Vespasian would give Jerusalem back to the rebels? I do not think so. Rabbi Akiva was a zealot who believed in “all or nothing.” To him it was better to die than to surrender Jerusalem. For him, the struggle for mere existence was a foolish, hopeless struggle. Years passed. Yavne saved Jewish culture, and the Bar Kokhba revolt failed. The messianic controversy seemed to be resolved—until the waves of Sabbateanism, Frankism, Zionism, and finally the war of “Iron Swords.”